Tools for Re-imagining Learning

Tools for Re-imagining Learning

Overview

What is this for?

This is a resource for trainers, curriculum and learning designers, and training leaders in the Singapore Continuing Education and Training (CET) sector. Our hope is to deepen understanding of teaching and learning practice to create innovative and enlivening possibilities for adult learners. We see the challenges as:

- Empowering learners to be more aware and responsible for their learning

- Developing creative learning and teaching cultures for innovative "outside the box" thinking

- Fostering growth of the whole human being

What is on this Website?

Meta-Cognition – Learn more about thinking about thinking.

Meta-Teaching – Reflect on your own teaching and learning practice.

Research – Discover resources to assist you in conducting your own research into your practice.

“Meta” Tools – Find practical activities and tools to use in your classes to build a culture of going “meta”, tapping into holistic intelligences.

Stories – Read about the journeys of other trainers and learning designers who used “meta” approaches in their practitioner research projects. These included exploring how to bring joy into learning, introducing peer assessment, providing better feedback for learners, and the being and becoming of teachers.

What is going "Meta"?

Going “Meta” is essentially thinking about how you are thinking, doing or learning.

- It helps us to stand back, pause and reflect on what we are doing, why we might be doing it and the underpinning paradigms and values.

- It helps us to step outside the expected way of doing things, see larger wholes, different meanings and new possibilities.

- It helps to build self-learning capacities, and improve critical thinking and self-regulation.

- It can develop discernment, appreciation, clarity, and a sense of purpose and alignment.

Dr Sue Stack explains what we mean by “going meta”:

Reflect | Expand | Create |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Where did these tools come from?

This website is based on an IAL research project, Tools for Learning Design (TLD), led by Dr Sue Stack and Dr Helen Bound in 2011 and 2012. The project involved nine training and learning design leaders in the Singapore CET sector. They explored what it meant to bring meta-lenses to their own practice as part of creating their own practitioner research project. The tools on this website were creatively developed in response to the participants’ needs and discoveries.

A Key Theme that emerged from this project was the importance of bringing the human being with us; utilising our full creative capacities including heart and soul. By growing ourselves we can grow the system to grow us. The tools that we use and the orientations that we bring play important roles in how we help our learners to be and to become.

Tools for Learning Design Report

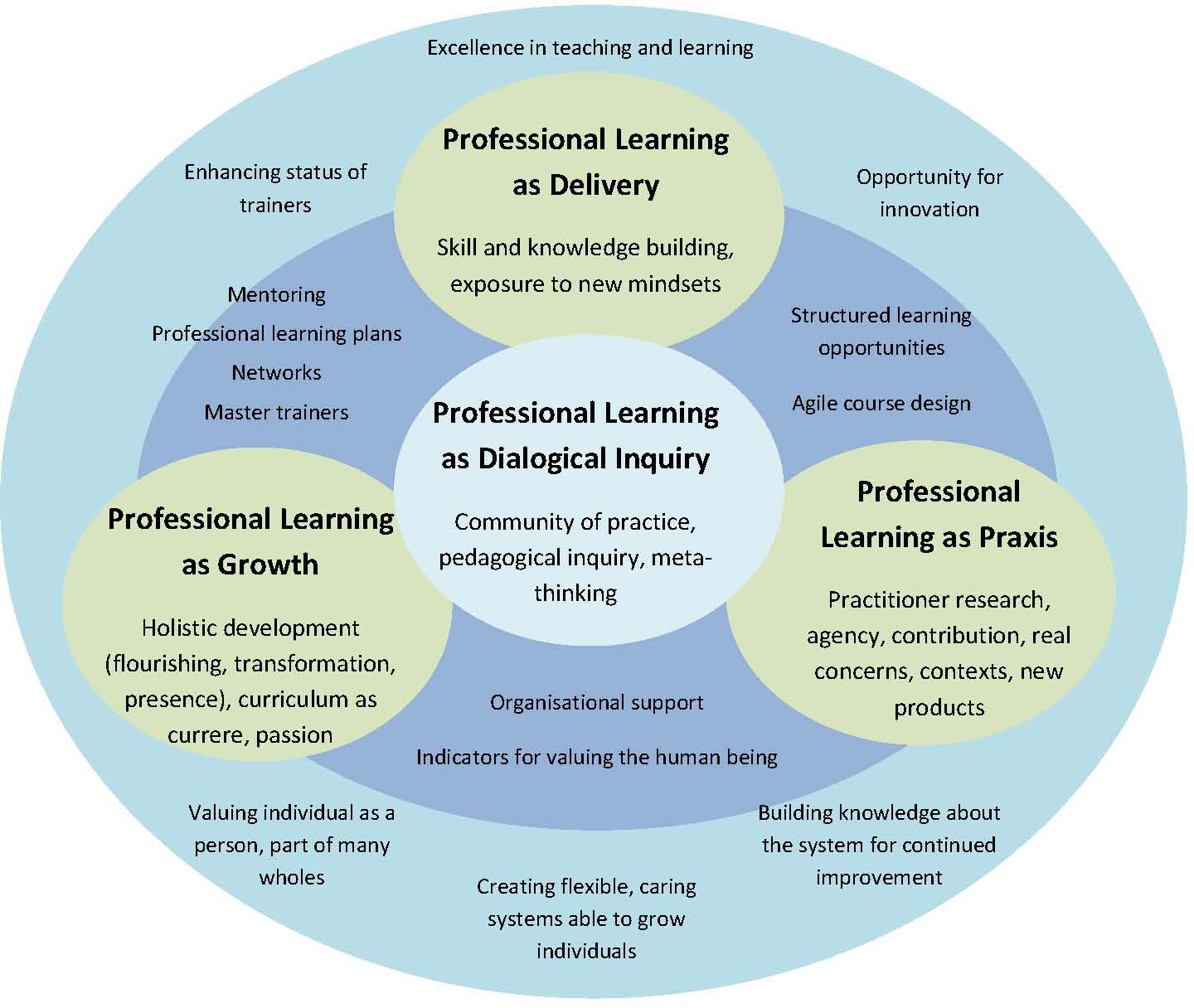

The Tools for Learning Design (TLD) research project aimed to explore how a professional learning model of integrating “meta” processes with practitioner-based research might deepen the pedagogical understanding of CET leaders, thus leading to greater innovation within their work contexts.

These comprehensive reports detail:

- The challenges in the Singapore CET sector that the project aimed to address

- The theoretical frameworks behind the programme

- A rich description of the programme

- The stories of the participants

- A thematic analysis

- Implications for professional learning

- Recommendations for the CET sector

TOOLS FOR LEARNING DESIGN RESEARCH REPORT

TOOLS FOR LEARNING DESIGN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Meta Cognition

What is Meta-Cognition?

"Thinking About Thinking"

Meta-Cognition enables us to stand back and to reflect on what we are doing, feeling and thinking.

In learning and development situations, trainers can use meta-cognitive processes to:

- Better understand how their learners are thinking and learning

- Reflect on their teaching and learning frameworks and approaches for continual improvement

- Enhance their learners’ appreciation of how they are thinking and learning.

Using meta-cognition in my classes opened up entirely new conversations. It enabled us to go deeper into the material, and help us better understand each other.

– TLD Participant

How do We Teach Meta-Cognition Processes?

- Use or create some meta-cognitive tools or routines.

- Start simple. Consider asking your learners “What are you thinking? How are you thinking about that?” Don’t be judgmental – just be interested in how they are creating meaning.

- Encourage learners to notice their thinking patterns and their preferred ways of learning or doing things.

- Value reflection on learning and self-assessment

- Use or create some Meta-Cognitive Tools or routines.

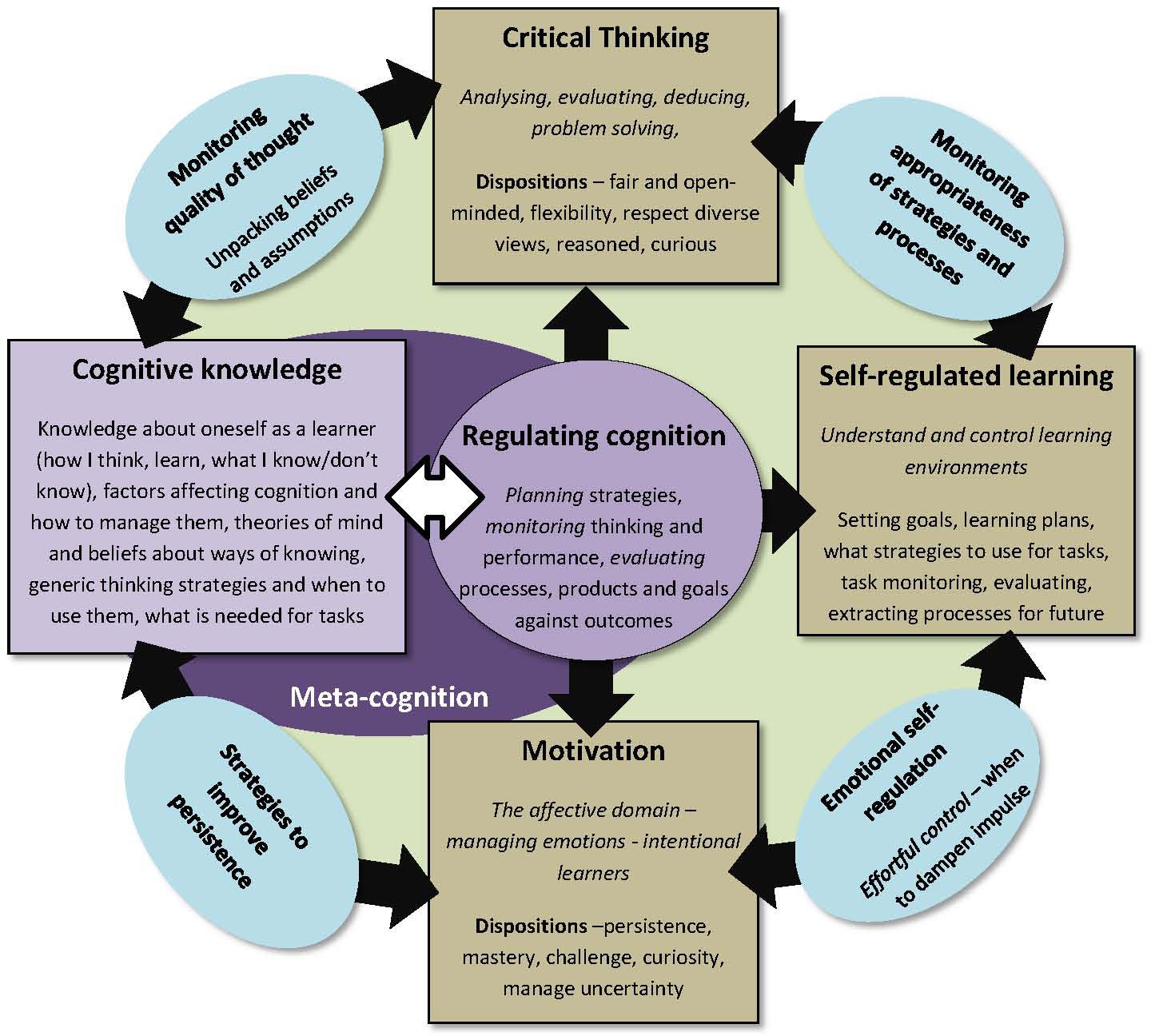

Understanding Meta-Cognition

For background information on meta-cognition to support teaching and learning, produced through the Tools for Learning Design (TLD) project, see Understanding Meta-Cognition (PDF, 0.5MB).

The content includes:

- What is meta-cognition?

- What are strategies for building meta-cognition in learning situations?

- How might different orientations to teaching and learning help us to frame meta-cognitive questions?

- What issues do we need to consider when using meta-cognitive tools?

For Further Reading

Costa, A. L. & Kallick, B. (2004) Assessment Strategies for Self-Directed Learning California: Corwin Press

Meta Teaching

"Reflecting on Teaching and Learning"

What is a teaching session or design element that you have done recently that you are most proud of?

How would you describe yourself as a teacher or learning designer?

Our Biggest Tool is Our Own Mind

We each bring specific mindsets about the nature of learning, learners and teaching that act as different lenses in the way we interpret or imagine curriculum or learning activities. Our mindsets can come from our own experiences as learners, our hard-won knowledge as teachers, teaching or training courses, our personal values and theories, as well as from expectations of the system, procedures, cultural practices and values.

Making the Tacit Explicit

As we build up experience in teaching or learning design much of our knowledge becomes tacit – the submerged part of the iceberg. Without tacit knowledge we would be overwhelmed by trying to keep too many things in attention. However, over time our tacit knowledge may need to be re-examined and renewed. Our enculturation into systems and cultures may have led to unquestioned assumptions and paradigms that shape our mindsets and underpin our practice.

Re-examining Our Tacit Knowledge through going “Meta” can:

- Provide us with language to talk about what we do

- Free ourselves from habits that no longer serve us and help us revitalise those things we deeply value

- Deepen our understanding of teaching and learning

- Open ourselves up to other paradigms and ways of doing things that yield innovative practices

- Help better align our purposes, values, practices, questions and opportunities.

Reflecting on the “Who” of Teaching

In November 2011, as part of a Tools for Learning Design participant’s project, 14 trainers engaged in a workshop to surface some of their tacit teacher “knowledges” and tensions. The PowerPoint below shows some of the simple holistic activities that were used as part of a process to stimulate deep conversations about the being and becoming of teachers.

The Complexity of Teacher Practical Knowledges

Teacher Practical Knowledges, introduced originally by Shulman (1987), is the notion that there are many “knowledges” that teachers need to master. In the following diagram these are listed in the inner circle. In the outer circle are the types of “meta” questions that can help make these tacit knowledges more explicit.

These different knowledges are deeply entangled with each other, so by trying to change or develop one aspect, other aspects are often challenged or may resist transformation. Being aware of the complexity of these enables us to be more mindful, holistic and kind in the way we think about expanding our practice and ourselves.

What can Help Me get a “Meta” Perspective of My Teaching Practice?

- Considering and experiencing alternative teaching and curriculum paradigms can help in understanding which teaching orientations you most draw from, and give you fresh lenses and questions to interrogate your practice. The Orientations to Teaching (PDF, 0.4MB) resource provides a self-paced guide to reflecting on the different teaching roles you take, enabling you to map your orientations to different teaching metaphors. However, this is no substitute for direct experience of other teaching paradigms.

- Autobiographical writing or drawing maps about your journey as a learner and a teacher provides an opportunity to remember key experiences which shaped your beliefs and values, and gives you the opportunity to re-examine them. Asking who inspired you as a teacher or mentor helps you reflect on those values that you are likely to be aspiring to in your own practice. It may help to have frameworks or questions to provide some alternative lenses in interpreting your journey.

- Critical friend dialogues are a valuable form of reflection for those who think best when talking with another, rather than through personal writing. A critical friend helps you to tease out your concerns and issues, gently asking you to look deeper at assumptions. They help you to articulate your tentative theories and what you value, encouraging consideration from different perspectives. They might capture on paper your journey through words, maps, images or metaphors to help you test what you really mean.

- Using powerful reflective frameworks can help provide novel lenses in thinking about what you are doing. For example, Seven Ways of Inquiry and Triple Loop Learning are not just about providing a set of useful questions, they are about moving into alternative holistic intelligences or spaces from which to inquire. We can fall into patterns of questioning and it helps to have frameworks to remind us to go beyond our comfort zones.

For more information, see

Practitioner Research Resources (PDF, 1.2MB)

- Critical incident reflections help to keep alive inquiry into one’s own “living theories” of education. Start writing about an incident that was uncomfortable for you and is still unresolved. Write a description, illuminate the tensions, and start looking deeper for the reasons behind things. What are some inherent assumptions about the learners, expectations, power relations, or underpinning culture? What new way of framing what was happening might yield other interpretations? What do you deeply appreciate that is surfacing from this inquiry?

- Getting insight into learners' learning experiences. There is an art to making students comfortable enough so that they can share with you what is really going on for them, particularly in a culture where students respect the teacher and will stay quiet rather than seem critical. It is important to be non-judgemental, and being interested in what they are thinking and feeling as part of developing better learning experiences for everyone. Brookfield’s questionnaire for students can be a good icebreaker leading to more open “process” conversations about the learning.

| ||

References

Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-23

"Meta" Tools

“Meta” Tools to Use with Learners

“Reflect – Expand – Create”

What does a good “Meta” tool aim to do?

“Meta” tools (processes, activities, mindsets) help the teacher, student or learning designer make the invisible visible – expanding what is seen. A good “meta” tool aims to:

- Lift people into a space where different conversations are possible

- Help people investigate more deeply and critically into the “behind the scenes” principles, dynamics or processes of their domain

- Help people to better understand their own values, thinking, learning, ways of framing, relating and development.

Tools for Learning Design (TLD)

Participants described three states of experiencing “meta” (here).

Dialogical – flexibility in stance, seeking deeper understanding and potentials through inquiry. Finding more imaginative wholes.

Discernment – being more aware of the different lenses they are bringing to an issue. It includes asking “How am I being positioned? What is my frame here, what are the origins of others' and my views?”Finding clarity.

Mindfulness – more in tune and connected with what is happening. This means noticing others and one’s self, being authentic yet self-aware in the moment. Finding connection.

Using Common Tools

There are many generic and industry-specific tools, models or processes that can help build a greater “meta” awareness. Some generic tools include de Bono’s 6 Hats, Integral Learning, Action Logics, Habits of Mind.

Frameworks or processes like these provide shared mental models enabling a group to build on a common language and set of processes.

However, while many people benefit from using pre-made tools, often the most effective “meta” process is the thinking that someone does in adapting or creating models, processes or schema for their own and others’ understanding.

“Meta” Tools have a Timeliness

“Meta” tools are not necessarily “true” representations of reality, rather a stepping stone for a particular stage of someone’s journey.

It is important to know when a tool becomes too limiting and to let it go. A wide selection of tools enables people to pick ones that are most suitable for them or for their group.

Building Your Capacity for Using and Designing “Meta” Tool

If you are not used to going “meta” with your students, then it can seem a little strange and challenging to do this. It may take a little time to build a culture where people are happy to talk or write about their thinking or their processes.

However, by starting small, practising with some simple tools and refining your processes, you will soon find yourself modifying or creating new tools.

Judging the Affordances of a “Meta” Tool

Here are some questions to ask:

- Will my students understand it? Are the language, intent, structure or process clear?

- Is it plausible for now?

- Is it useful? Does it expand possibilities or build capacities? Can it be adapted by the teacher or the students? Is it memorable and does it link into preferred ways of learning?

- How does it position us? What assumptions are we falling into? What are we missing? How does it limit possibilities?

We focus on the tools that the teacher uses for the student, what about the tools that students use and could create for themselves?

– TLD Participant

What tools enable students and their teachers to better watch what the learning is that is happening?

– TLD Participant

Our Biggest Tool is Our Own Mind

Our mindsets, formed by our experiences, values, paradigms and culture, shape how we interpret and utilise “meta” tools. To illuminate some of these mindsets go to Meta-Teaching.

Resources

Tools for Learning Design Project

During the Tools for Learning Design project we developed and used a number of "meta" tools specifically to encourage participants (teachers, leaders and learning designers) to reflect on their own practice. We have included some of the more generic tools below. We believe these can be adapted for other training contexts with adult learners.

Holistic Reflection Strategies (PDF, 1.2MB)

This collection of 17 reflection strategies use different holistic intelligences for:

- Capturing thinking in the moment

- Reflecting on learning

- Making values explicit

- Exploring tensions and dilemmas

Dialogical Inquiry (PDF, 0.6MB)

This is a framework that facilitators can use with students to help them better understand their learning and inquiry styles.

Facilitators can use the framework to improve their own questioning and feedback practices.

Learning designers can use it when considering design of learning activities.

Editable version of dialogical inquiry model:

Profile (Word, 80KB), Case Study (Word, 60KB)

Surfacing Assumptions (PDF, 0.4MB)

This is a gentle activity to help people reflect on the assumptions that they might be bringing in their practice or thinking.

It helps people explore alternatives by imagining circumstances where an opposite of an assumption might work.

It provides a shared language and expectation.

Ecology Room (PDF, 0.5MB)

This learning activity juxtaposes multiple activities together in a classroom “eco-system” that enables iterative learning, feedback, diversity, depth and emergent understandings.

This is a powerful activity when considering complex, inter-weaving issues and can provide turning point stimulus in courses or workshops.

See the PowerPoint (PPT, 4.3MB) of The “Who” of Teaching workshop which used this approach.

Using Space to Encourage New Perspectives (PDF, 0.3MB)

By making the room a stage with different spaces representing different perspectives students can engage in a different type of dialogue.

Students sitting in different perspectives in conversation with others get a better sense of their perspective and its implications when it rubs up against other perspectives.

It is highly useful when you wish to make visible hidden perspectives.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the participants of the TLD project and The “Who” of Teaching workshop whose willingness to experiment has enabled the development of these activities, guides and examples.

Practition

Do you have a desire to improve an aspect of what you do, or solve an issue in your workplace?

Where would you like to be stretched?

Why do Practitioner Research?

Practitioner research enables you to address a concern or try out an innovation in your own workplace.

- It contributes to the improvement of the organisation or the system.

- It builds your skills and understanding in the context of your workplace, providing effective professional learning.

- It can link to your own passions and concerns.

- It builds research capacity in your organisation.

- It can engage colleagues and managers in a structured approach to exploring an issue, enabling the generation of rich evidence, deeper understandings and imaginative possibilities.

I have never been involved with a research project like this before. While I value the professional learning that I am getting, I also very much want to feel that I have contributed to something beyond me, that my involvement in this project can help change things for the better.

– TLD Participant

Which Type of Practitioner Research Suits Me?

Practitioner research is a well-established research field. We suggest two models:

Action Research – “Plan – Act – Reflect cycles” (see picture). Suits active experimenters who can try out interventions and gain feedback for continuous improvements.

Design Study – Get data to discern an intervention. Suits more reflective learners who seek to understand the issues more deeply before designing an intervention.

It does not matter if you have never done research before. The aim is to start simply and then build up to more complex and rigorous approaches.

The Role of “Meta” in Practitioner Research

Effective practitioner research lies in the ability of the practitioner to move beyond the immediate and pragmatic question “How can I improve this?” to understanding more deeply the tacit assumptions, values and paradigms in which they are embedded. A “Meta” lens enables:

- Reframing of the problem or question

- A better appreciation of what is valued

- A deeper understanding of how different research methods might reveal different perspectives on the problem

- An expanded view of what might be possible.

What Workplace Support is needed to Undergo Practitioner Research?

While practitioners can engage in research on their own, greater impact can be achieved by engaging with different stakeholders (team members, managers, learners, employer groups) during the project. This helps to build dialogical inquiring communities, creates buy-in and takes everyone on a journey.

Where do I start?

- With a concern that you want to address.

- Gain support from your team and manager, and if possible recruit some of your colleagues as co-researchers.

- Use the resources on this website to help you in reflecting on your assumptions and values, and deciding on your research approach.

- Recruit a critical friend to help you tease out your research question, and be available to help you reflect along the way.

- Invite stakeholders to be part of a dialogical community to discuss what is emerging along the way and be part of generating future plans. Consider early scheduling of meeting times.

- Consider whether you would like to link into an IAL course, mentor or community of practice to provide support.

- Work out a plan of action for gaining initial information and for implementing your intervention… and then go for it.

.jpg)

Resources

Practitioner Research Resources (PDF, 1.2MB)

This introduces the concept of practitioner research and provides particular tools or guides for helping to conduct the research – clarifying the question, literature reviews, ethics considerations, interview techniques, surveys, reflective practice, critical friends, dialogical communities and suggested further reading on research methods.

What is My Concern? (Word, 30KB)

This is a template to help practitioners think about and plan the scope of their study.

For further information about the Tools for Learning Design (TLD) project see the Report (PDF, 3.9MB).

Stories

Trainers’ Stories of their Research

Below are summaries of the individual practitioner research projects undertaken by participants in the Tools for Learning Design (TLD) research project. For five of the participants we have created more detailed stories that convey their questions, issues, processes and journeys.

The participants have kindly shared their emotions, vulnerabilities and difficulties in order to tell a larger story of perceived constraints, opportunities and cultures, and the nature of such transformative journeys.

The stories are slightly fictionalised with changed names to provide anonymity. They aim to express the authentic voice of the participants through using a conversational writing style.

Writing up Practitioner Research:

- What is my concern and why?

- What are the tensions and contradictions that I am facing?

- What was my approach to exploring these activities?

- What have I discovered?

- How have I changed?

- What do I now value or understand?

- How has my practice changed?

Joy of Learning

Bill was interested to find out how the joy of learning can enhance learning in his classes. He used Brookfield’s critical incident questions (1995) in his classroom to find out how his learners (trainers in other organisations) were experiencing the module and the way it was being taught. He also reflected and journalled about his aims, dilemmas and experiences in his classes, which he shared with his learners. This resulted in increased openness, sharing and participation between members.

As he let go of the expectation that he had to be perfect as a teacher and know all the answers, he became increasingly authentic. Bill built strong, meaningful and mindful relationships with his learners who deeply valued his authenticity and the modelling of different approaches to teaching. Through Bill’s modelling of the vulnerable reflective practitioner, his learners were also inspired to deeply reflect on who they are as trainers and to involve their own learners in reflective processes.

Download Bill’s Story (PDF, 0.2MB) to read more.

Exploring Peer Assessment

Philip started with tackling the idea of introducing peer assessment in his programming course in order to give students greater power in the assessment process. Through thinking about the goals he wanted peer assessment to achieve, he developed an understanding that teaching skills in small bits does not develop the vocational identity of being a programmer, but only develops an incomplete set of programming skills.

He developed a set of questions to get insight into his students’ thinking and experience of the course which helped him better craft his delivery of the course. Through the building in of conversations and reflections about learning strategies and thinking as part of student work, students have gained a greater awareness of the processes they use and are now able to see other points of view.

Download Philip’s Story (PDF, 0.2MB) to read more.

Improving the Quality of Feedback for Students

Anita began the journey to develop feedback skills of her nursing clinical facilitators by bringing them together. She asked them to reflect and write journals as they worked with students in the field. They used one of the workshop’s tools for learning, the dialogical inquiry model, to prompt deeper reflection about the sort of feedback given.

It became evident that there was a tendency to scold the students – to see them as having weaknesses to be corrected. By seeing this as just one paradigm of learning (teacher-centred), Anita could then consider other paradigms to provide alternative ways to construct feedback, for example, student-centred (concerned with the development of students and their perspectives) and subject-centred (conversations that enable both the teacher and students to gain new insights) paradigms.

Download Anita’s Story (PDF, 0.6MB) to read more.

Bringing Constructivism and Humanism into the Design of Modules

Fettia originally intended to explore how to bring constructivist and humanist principles into the design of some new modules. Her organisation was in a process of getting a large number of new modules ready for accreditation with the national agency overseeing quality assurance for continuing education and training. The limited timeframe, the demands of the process, including the amount of documentation required, and her lack of experienced staff meant that she found herself unable to create time and the team to consider the modules from these new perspectives. Further, she herself felt dehumanised by the dynamics of the situation.

Her story highlights some of the barriers to change and how, although some ease may be found through one or two strategies (e.g. help by mentoring), it takes a much broader strategic approach to break the cycle of continued practice.

Download Fettia’s Story (PDF, 0.3MB) to read more.

The Being and Becoming of a Trainer

Michelle was interested in why and how trainers become trainers and stay in the profession, what makes a good trainer and what challenges they face in their careers. She used one of the tools for learning processes, the “ecology room”, as a way of eliciting information from a group of trainers through their responses to a range of activities. The emerging rich set of artefacts, values, stories and perspectives surprised Michelle, exposing the human face and the importance of considering the “being and becoming” of the teacher/trainer when devising strategies for the professional development of trainers.

This project helped Michelle to weave together her PhD studies with her own work role in the professional growth of trainers. From this, she hopes to tell the stories of the “being and becoming” of trainers to help inform system development.

Download Michelle’s Story (PDF, 0.4MB) to read more.

Better Assessment Access through Technology

John’s original intent was to develop assessment tools that integrate learning across and between modules. The implementation of this idea fell through; he believes that it would require time-consuming and difficult negotiations with the national agency overseeing quality assurance for continuing education and training. Instead, he introduced Skype as a means to save participants the trip to the provider’s premises to undertake the assessment. Even so, for the pilot, participants had to go to the provider’s premises because he understood that it would otherwise be a breach of the quality assurance rules that require face-to-face assessment.

Theory/Practice Divide

Marie initially aimed to get an understanding of her trainers and their students through administering questionnaires which gave frank and illuminating answers. This highlighted some key areas that could be improved. One of these was the divide between the theory and practice of learning from having one day of practical and one day of theory, which was tedious for both students and trainers.

A first step was breaking these into half days. A key insight was about her trainers – although elderly, they still had a desire to learn new things. This, then, opened the way for introducing the use of iPads in the practical classes for reference to theories and bridging some of the theory/practice divide.

Evaluation of DACE

Jimmy took the opportunity to design a multi-probe evaluation of the Diploma in Adult and Continuing Education (DACE) programme which he had been partly responsible for in its delivery, design and management. Using a mixture of questionnaires, investigation of artefacts and focus groups, he collected evidence that suggests that DACE has achieved not only what it originally intended – in developing the professionalism and capacity of trainers beyond the Advanced Certificate in Training and Assessment (ACTA) programme – but has also developed strong and enduring peer relationships and community of practice.

These communities are important cohorts that can be targeted for continued professional learning and dialogue. Through the project, Jimmy was able to better articulate his own values and identify the need for the system to grow individuals to grow the system, and to see himself as the human face of the system, providing space for others to grow.

References

Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Resources

- Tools for Learning Design Research Report (3.9MB PDF)

- Holistic reflection (1.2MB PDF)

- Dialogical inquiry (600kB PDF)

- Surfacing assumptions (400kB PDF)

- Orientation to Teaching (400kB PDF)

- Ecology room (570kB PDF)

- Using space to encourage new perspectives (760kB PDF)

- Understanding meta-cognition (540kB PDF)

- Practitioner Research Resource (1.2MB PDF)